On my walk to work I try to scan my NHS pass at the traffic lights – that’s how tired I am! I call in at a cafe, get coffee and a pastry, and try to push away the thought that the cost is equal to half-an-hour of work at my Band 5 salary. I should have made breakfast to bring in, but I fell asleep on the sofa last night.

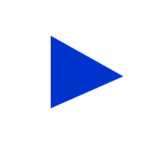

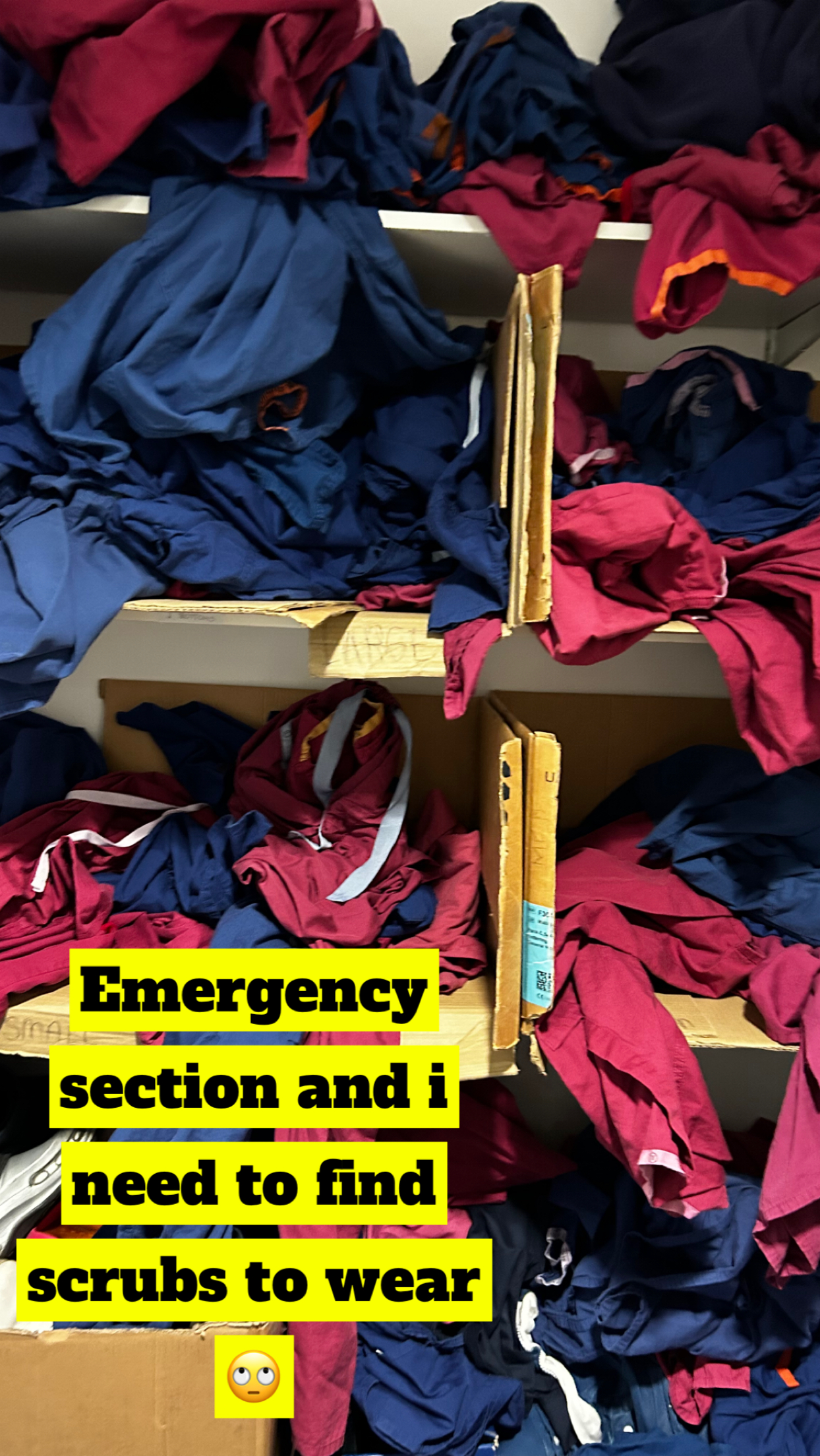

I step onto the ward; everyone I pass says hello. I am thankful to work with such lovely colleagues. I go to get scrubs and see almost empty shelves, which usually means it has been a busy night. I pull XXL bottoms over my small frame, and pray they don’t fall down during the day!

I trudge alongside my bleary-eyed colleagues to the midwives’ station. People say hello to me with their ketotic, coffee-scented breath. The board is chock-full of patients, with scarcely enough midwives to care for them all. As a newly qualified midwife, I always have a tinge of anxiety at this stage: who will I be allocated to, and will I feel capable of coping with whatever lies ahead of me?

I am immediately sent into the room of a woman who is pushing. I take a verbal handover, but it is impossible to write a full history or check her blood results on the computer. In between contractions I try to quickly build rapport with the couple. The next thing I know, the doctors and midwife in charge are here for the ward round; they seem annoyed that I don’t know her latest blood results and that I haven’t yet examined her. I’ve been here for ten minutes! The midwife in charge has a stern word with me about the couples’ luggage blocking access to the Resuscitaire. I feel like I’m drowning. The doctors examine the woman, confirm the baby is in a good position for birth, allocate us 15 more minutes to push, and leave.

My head is swimming; the CTG appears normal… should I have asked for more time? What position can I try next to help her to have this baby safely and quickly? I try to ask the couple if they are happy with the plan, but here comes another contraction… the head is visible. In vain I press the call bell for a second midwife, though I know that usually nobody is free to help. Do neonatologists need to be present for the birth? What are their birth preferences? What was the partners’ name again? Is there Syntocinon in the room? Do I hear a deceleration in the baby’s heartbeat? My eyes flick to the notes, where I still haven’t written a single thing…

My heart lifts when one of the lovely Band 6 midwives enters the room; she gets the notes and scribes for me whilst I assist the birth. I can relax and focus on the task in hand. The baby is in good condition, the parents (and myself!) are elated. It all went smoothly!

There’s no time to relax though. After delivering the placenta, I check her perineum and it needs repairing. I am gaining confidence with suturing, but the tear is deeper than I’m used to and I could do with some support.

I call again; another midwife comes and I explain my plan for the repair and she agrees. She cannot stay as she herself is giving one-to-one care. The tear is bleeding so I know I need to start. It takes a long time; I wish someone was available to look over my shoulder. The baby starts crying and the parents want to feed. I am sweating. I ask them to do skin-to-skin and I will help them to breastfeed once I have finished.

It’s now been an hour and a half since the birth and the feeding is delayed for no good reason; if only there was a spare Maternity Support Worker to help, but there’s only one on the ward today and she has several beds to clean. I finish suturing, and get the baby on to the mothers breast. The midwife in charge knocks on the door and asks how long I’ll be as she needs the room. I lie and say “soon”. I race to the computer to type up the notes. The couple ask me to take pictures of them, which, of course, I do with a smile. I look at this incredible, beaming person who I’ve assisted to birth their child. This part of the job is so gratifying.

I manage to get everything ready to transfer them to the postnatal ward, when the woman asks for a shower. I feel myself getting annoyed; that will take at least another 15 minutes and the midwife in charge must already think I’m so slow! Then I catch myself: of course she wants a shower, wouldn’t I?! I feel ashamed. I smile and help her to shower – she says how much better she feels, and I do too.

When I return from taking them to the postnatal ward, it is midday. I am sent for lunch, which I am glad of. I gulp my stone-cold coffee and wolf down my pastry in giant clumps, I’m so hungry! I try to relax; it’s only half way through the shift, and I feel like I have done a full day of work. This job can be so hard yet it is so fulfilling; even now, as my feet throb and my head aches, I am still glad I left my previous career to do this.